Iris Chang's many truths

December 8-9, 2007, The Weekend Australian

January 26, 2008, Sunday Star-Times magazine

The motorist who went to investigate the white Oldsmobile parked just off highway 17, which runs between San Jose and Santa Cruz in Northern California, was a county employee. It was just after nine on a November morning in 2004 and he had spotted a female driver who was either asleep or in trouble.

As he walked towards the car, he might have been able to see that she was young, very beautiful, with long black hair and porcelain skin.

But she wasn’t drowsing. That was the tragedy. Her mouth was bleeding, her clothes were blood-stained and an ivory-handled antique gun that had been fired lay beside her. She had been dead since dawn.

Her name was Iris Chang and she was just 36 years old with a celebrated life that most people believed had been perfect. When news broke of her death, motorists in the United States pulled into the roadside in shock to listen to their radios.

Chang was a best-selling author of enormous repute, brilliance and charisma. She had a husband who was a successful engineer at Cisco Systems, and a two-year-old son, a close and loving family and wealth.

She also had some notoriety. As fragile as she looked, she had repeatedly taken on the governments of both Japan and the US as she shone a light on one of the darkest moments of the 20thcentury. Seven years earlier, her book, The Rape of Nanking – The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II, had appalled a world that might have been fully informed of German war crimes but knew far less about those in the Far East.

Iris Chang’s book was published on the 60th anniversary of the largely forgotten massacre; it caused a furore. She was 29.

Chang’s book is nightmarish in its descriptions, like a handbook from hell, and her fierce outrage is on every page. All this from a woman who had once been a college homecoming princess and was just 29 when her book came out.

She had chronicled how, on December 13, 1937, in the Sino-Japanese war that preceded World War II, the Japanese army had captured the Chinese city Nanking. Between 100,000 and 300,000 were murdered in horrific circumstances during seven weeks of deliberate terror. Thousands of others were tortured in ways that seem almost unimaginable. At least 20,000 women, perhaps 80,000, were raped and most of them were murdered too, again in ghastly ways.

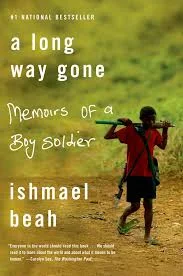

An image that accompanied publication of this story in The Weekend Australian.

For six decades though, the events of 1937 had been virtually forgotten by the world at large. Mostly, the terrible stories had been passed down through generations of Chinese families. The Rape of Nanking, published on the massacre’s 60thanniversary [starting December 13, 1937, it lasted for six to seven weeks, into 1938], was the first to bring the story to a mass English-speaking audience. It has since been translated into 15 languages and has sold half a million copies.

Her agent and former editor, New Yorker Susan Rabiner says Chang didn’t just have best-seller fame, she had Joan of Arc fame. Dale Maharidge, a Pulitzer prize-winner who teaches at the Columbia school of journalism, remembers how his Chinese and Chinese-American students venerated her. “She was like Jesus Christ resurrected to one of them,” he says now.

Nanking was actually Chang’s second book. An over-achiever from childhood, she had landed her first book contract when she was just 23. She wrote three ground-breaking books altogether and all had a similar theme, says a close friend, Barbara Masin. It was Spartacus, the lone individual standing up against evil might.

Poignantly, her mother said last year that her daughter had always intended to write at least ten books in her lifetime.

But then she was gone.

A coroner declared it suicide.

Another mystery story

The revelations about Nanking had brought Chang acclaim, a high point on a trajectory to the top that had started when the daughter of two prominent Chinese scientists, who had escaped to Taiwan from China before moving to the US, wrote her first mystery story at four. But did the Nanking book also start Chang off on another trajectory, the one that eventually led to that silent car on the country road?

One of her college friends, Paula Kamen, who had studied journalism with her at the University of Illinois, was shocked powerfully by the death. She entered a nightmare of her own. Chang had made several efforts to contact her just before her death but Kamen had let one call go to voicemail and been tardy in replying.

When they finally spoke, Kamen was surprised to hear her highly energized, normally ebullient friend sounding lost, depressed, sad. “Paula,” she said. “I have something to tell you. I have been very, very sick… And I just wanted to let you know that in case something should happen to me, you should always know that you’ve been a good friend.’

Alarmed, Kamen asked her friend more questions. Chang sounded a bit spacey, anxious and fearful. She was worried about the magnitude of her next book – it would have been her fourth -which was to be about the Bataan death march of 1942 when 90,000 American and Filipino soldiers had been brutalized by their captors, the Japanese army.

Again, she was worried about the controversy the book would stir. And again, the tales of barbarity were almost unimaginable. A stenographer transcribing Chang’s tapes could not stop weeping as she listened to the frail, aged veterans’ accounts.

Iris Chang at a 1998 book signing. Intense and aggressive attacks from Japanese militarists affected her deeply. Photo courtesy of Ying-Ying Chang

In 1998, in an email exchange, Chang had told a CBS News broadcaster in Seoul, Victor Fic, “not a single week goes by when I don’t suffer harassment from some vicious right-wing Japanese group”. Now she said flatly to Kamen, “People in high places are not going to like it. Frankly, Paula, I fear for my life.”

Haunted by that conversation, and also by her failure to speak to Chang again before she suicided three days later - Kamen wrote a eulogy to her friend on the web-zine, Salon. Surprisingly for a eulogy though, it was a paean to overcoming jealousy of an extraordinary person. The first email that Kamen received afterwards, of hundreds, was from another historian in Chang’s field who said he too felt guilty because he had been jealous for years. “Don’t feel bad,” Kamen replied. “Everyone was jealous of her”.

The huge response convinced Kamen to write her own book: Finding Iris Chang – Friendship, Ambition and the Loss of an Extraordinary Mind. It has just come out in the US and will be published in Australia and New Zealand early this year [2008]. A kind of psychological memoir crossed with a detective story, the book sometimes reveals more about the author’s demons than it does about Chang’s.

Immediately after Chang’s suicide, websites sprang up questioning whether the controversial author had really been assassinated.

Her story turns out to be more painful.

One version of this story appeared in the Sunday magazine of the Sunday Star-Times newspaper in New Zealand.

Chang’s parents – her mother Ying-Ying was a microbiologist, her father a physicist and both worked at the University of Illinois – had told her she could choose to do anything she liked so long as she excelled.

Years later, Chang used to jokingly refer to herself as the “Iron Chink”. That was the name, if reflective of the politically incorrect times, given to a fish-gutting machine invented in the early 20th century. It had taken over the work originally done by Chinese immigrants to the US whose capacity for working long hours at a tough pace was legendary.

“Iris could always travel more, go without sleep more than anyone,” says Kamen. The resilience paid off. As Maharidge, an early writing mentor, told me: “She went big, fast, young.” He described her style: “She was a very, very, very, very fast thinker. An hour goes by [in conversation] and you’ve covered 15 points, not just three or four.”

Chang had always had plenty of friends but after her death, it turned out that some had had less to do with her in recent years. Her reputation for focussed telephone conversations that could last for hours had exhausted them, they guiltily explained. Ironically, some friends also felt their own imperfect lives didn’t match up to Chang’s.

All her life, Chang had surprised people with her focus, looks and, most of all, her directness. When her husband-to-be, Brett Douglas, once asked her, while still in college, what her chances were of writing a best-seller, she airily answered: “Ninety percent.”

Such traits and gifts come with a hefty price-tag. Chang continually attracted envy, and also suspicion. Her mother can remember her young daughter in tears. Sorority sisters meanly nicknamed her “Changalang” behind her back, as in, being a “dingaling”. Chang had wanted to fit in at school and college, but didn’t. Still, one year, she ran for homecoming queen and made it to be one of ten princesses.

And of course, once Chang became famous, she moved easily among other celebrated achievers who had no reason to be jealous of her. In all likelihood, they were probably just as prone to behaviour that might seem odd to others but which to them, simply ensured their success. Chang, for instance, had never hesitated to ring famous writers to get their advice. She dreamed big.

Chang was even able to put the then president Bill Clinton in his place. When, after the success of her Nanking book, she and Brett met him on the red carpet, Chang didn’t just shake hands. She insisted that the president pose with her husband in a photograph, moving him closer to Brett and impatiently waving the Secret Service men out of her camera’s frame. In the picture Clinton wears a dazed but amused grin.

“I was truly a devil”

As a little girl, Chang had heard stories about Nanking – her own maternal grandparents had escaped - but she was baffled when she could never find out more in the public libraries. Then, as an adult, at a conference, she came face to face with photographs taken during the city’s capture: “Nothing prepared me for these pictures – stark black and white images of decapitated heads, bellies ripped open and nude women forced by their rapists into various pornographic poses...”

Chang wrote of her decision to do the book: “I was suddenly in a panic that this terrifying disrespect for death and dying, this reversion in human social evolution, would be reduced to a footnote in history… unless someone forced the world to remember it.”

One participant Chang interviewed, by then an elderly doctor in Japan whose waiting room held a shrine of remorse, confessed to her that babies had been bayoneted and thrown into boiling water and women gang-raped: “I beheaded people, starved them to death, burned them, and buried them alive, over 200 in all. It is terrible that I could turn into an animal and do those things. There are really no words to explain what I was doing. I was truly a devil.”

Her book was not an attack on a nation, but on a particular militaristic culture that had flourished at a particular time. Her theme was “the power of cultural forces to make devils of us all, to strip away that thin veneer of social restraint that makes humans humane, or to reinforce it.”

She also coolly demanded that Japan issue an official apology, pay reparations and properly educate future generations about Nanking instead of dismissing it as an “incident” or worse, as “the so-called Nanking massacre”.

Her stance infuriated elements of the Japanese government and the extreme Right in Japan and her book was savagely criticized. A Japanese comic book portrayed her as a drooling harpy rallying white people against Japan. The Japanese ambassador to the US, Kunihiko Saito, called a press conference in Washington in early 1998 to criticize the book but Chang seemed unstoppable. Eight months later, on American Public Broadcasting Service’s NewsHour,a remorseless Chang took Saito on for not making a sincere apology from the heart.

“Her parents were petrified that she’d be seen as disrespectful,” says her agent, and former editor, Susan Rabiner. But the Chinese-American community was delighted.

Attempts to “bury” Chang’s work were thwarted by her fierce defence and, after her death, this documentary film.

Japanese officials and academics questioned her facts and interpretations, and it was true there were minor errors in dates and names. “Most academics are critical [of Chang’s book] in some ways,” says Australian National University’s Tessa Morris-Suzuki, professor of Japanese history. “There were quite a lot of little mistakes, mostly odd things about names and dates not being quite right and that was a shame.”

Nevertheless, Chang’s book was very significant, she says. “It really put the issue into the consciousness of a lot of people in the United States and because it sold well there, it stirred up a lot of controversy and debate in Japan.

Says Morris-Suzuki, “The right wing has become more and more vocal in Japan in the last ten years. If you type ‘Nanking’ into google, you’ll get millions of entries, many completely denying the massacre, saying all the photos are forged, quite ridiculous things, and awful things about Chang too.

“A number of Japanese political leaders have apologized [for Japan’s war crimes] but what’s missing is a strongly worded apology that’s a cabinet decision, a collective apology by the Japanese government.

“And that should be followed up with individual compensation. But one of the things that worries me is the longer they leave it, the more difficult it is for the Japanese government to make such an apology.”

But often, the reactions to Chang’s book were so extreme as to be senseless. Some critics maintained – and still do – that maybe “only” 20,000 had died in the massacre. Others maintained – and still do – that the massacre never happened.

That’s in spite of the fact that, apart from all the existing footage, photographs and records, Chang’s passion for archives had led her to an exciting discovery, a previously unknown collection of documents, notes and correspondence kept by an eye-witness, John Rabe, a German businessman and Nazi posted to the city at the time.

Instead, Chang found herself accused of Japan-bashing. Threatening letters arrived. Late at night, she would receive menacing calls asking after her husband and father. “How is Brett?” “How is Shau-jin?”

She was also under scrutiny from the United States government, worried about her effect on diplomatic relations. The truth is that for decades, the Nanking massacre had been “buried” for political reasons. The US had needed Japan as an ally in the Cold War against Russia and China and so hadn’t pushed Japan on war crimes as it had Germany. The Chinese government was embarrassed it had not been able to protect its citizens better. The hundreds of thousands of survivors, often injured and poor, stayed silent out of shame and because they didn’t believe anyone wanted to listen to them.

Chang did.

A change in Iris Chang

Chang had always been lively. Letters to Kamen were wryly funny. “And it was never mean laughter,” remembers Kamen. Barbara Masin says that talking to Iris had been like “jumping into an effeverscent fountain of possibilities”.But between 1999 and 2002, writes Kamen, something in the positive Chang started to shift. She and Brett tried to have a baby and after many miscarriages and fertility drug treatment, they had a son, Christopher. Around that time, some friends told Kamen they saw a difference, and Kamen herself noticed it. Either they were withdrawing, Chang was, or both.

Maharidge, who cared so much for Chang he doesn’t think he’ll be able to read Kamen’s book, tries to explain the intensity. “It was draining. She’d suck all the air out of the room.”

He had also been severely shocked when a frantic Chang had visited him in December, 1999, convinced that her bank records would be erased in the Y2K scare. Maharidge finally calmed her down, but at the end of an hour, she was still shaken. So was he. “I remember distinctly thinking, gosh, she’s mentally ill.”

He talks of the need for balance in writers: “I cautioned her, you can’t be ‘on’ all the time. Maybe you do a book on the homeless and then you do one on, I don’t know, Carribean vacation spots!”

Friends remembered Iris as “effervescent”. Her theme was always Spartacus; standing up against evil. Photo: Jimmy Estimada, courtesy of Ying-Ying Chang.

In early 2004, Chang did a frenetic publicity tour – 20 cities in 31 days - for her third book, The Chinese in America. Maybe it was finally too much. Her husband, Brett, said when she came back, she was different. Simple things suddenly became difficult, even depositing a cheque.

Then, in August, on a trip to Kentucky to interview Bataan survivors Chang had a breakdown described as a “brief reactive psychosis”. She hadn’t slept for four days and wasn’t eating. She was only briefly hospitalized but became convinced the government was trying to discredit her.

In September, she checked into a hotel with sleeping pills and vodka, but came home safely. Then, in late October, one psychiatrist diagnosed her with bipolar disorder or manic depression, a judgment Chang’s mother and father now dispute.

Kamen argues however that a combination of conditions – the destabilizing hormonal swings from the fertility treatment and failed pregnancies, as well as the depression that fertility drugs can reportedly cause – ran into a fault-line of exhaustion and stress, tipping Chang over.

The strong-willed, perfectionist Chang was appalled by the diagnosis and resisted treatment. Her psychiatrist recently told Kamen she was severely under-medicated when she suicided.

Iris wanted to be remembered as she had been before she was ill, that is “engaged with life”. She even once re-arranged then President Bill Clinton for a photo shoot, to his obvious amused bemusement. His security detail were waved away.

Depression still carries a stigma, especially in Asian societies. One Californian mental health service noted a doubling of the numbers of Asian women seeking help after Chang’s death. Kamen unearthed another secret. A rare condition was behind Chang’s many miscarriages so the couple used a surrogate mother to carry their biological child.

In early November, Chang carefully purchased three antique guns. Their age meant she escaped the standard ten day waiting period during which the California Department of Justice does background checks. Such a check would have revealed her psychiatric hospitalization in Kentucky.

The pain in Rabiner’s voice is apparent when she talks of her last conversation with Chang the night before she died. “She had lost her vibrancy; she used to be a high-energy, eyes-on-the-prize, tenacious person. Now she kept repeating what I said.” But she says there was nothing manic about Iris, at the beginning or at the end.

In a suicide note, Chang asked to be remembered as she had been before she became ill – “engaged with life”.

A mother fights back

Ying-Ying Chang, Iris’s mother, now retired from the university, doesn’t agree with the bipolar diagnosis. She wasn’t interviewed by Kamen – she initially said no and wasn’t asked again - and saw proofs just before publication. There was a disagreement over Kamen’s statements that Chang was definitely bipolar. “We think Iris’s situation was more complicated,” Mrs Chang says with dignified brevity. “It wasn’t as simple as bipolar. She was exhausted and didn’t have a chance to pull out of the depression.”

A family portrait for a birthday. From left to right, brother Michael, father Shau-Jin, mother Ying-Ying, and Iris. Photo courtesy of Ying-Ying Chang.

She also says Asians react to medications differently and that Iris was very slim which would have affected how the drugs worked. She is now writing her own book about her daughter [published in 2011, see end notes].

[Ying-Ying Chang emailed in mid-2019 to say that in 2017, the Iris Chang Memorial Hall was opened in China, in Huaian, Jiangsu, and that, at that time, the Iris Chang Park was under construction in San Jose. She has also established a website - http://www.yy.irischang.net/home/index.php - in Chinese and English.]

It is distressing to wonder if maybe it was the diagnosis itself, rather than what it diagnosed, that pushed a depressed, stressed and hormonally out of whack Chang to suicide. She died less than a fortnight later. We will never know. At the time, Chang’s suicide was seized upon by the fanatics as a signal that her book was written by someone unbalanced and therefore flawed.

That will be a harder position to take now that two new films are screening. Last December [2007], a documentary Nanking opened in the US. Inspired by Chang, it features actors Woody Harrelson and Mariel Hemingway narrating the diaries, letters and first-hand accounts of Europeans, like Rabe, who established an international safety zone in Nanking and saved hundreds of thousands of lives. Another new film, made in Canada, is Iris Chang: The Rape of Nanking which has so far screened in China and North America. [In late 2009, it was also shown in Japan.]

But meanwhile, a Japanese film called The Truth About Nanjing, claims the massacre was propaganda, a fabrication, and its director is reportedly supported by prominent Japanese politicians like nationalist Tokyo governor, Shintaro Ishihara.

Chang would have been outraged all over again.

Maharidge explains how he felt about Kamen’s research into his friend. “I didn’t really want to talk about Iris but I’m a journalist and I always want people to talk to me. I could imagine Iris perched on my shoulder, saying: ‘Talk!’”

Of all people, Chang understood the need to get to the truth.

This is a composite of two articles, originally written for The Weekend Australian and for the Sunday magazine of the Sunday Star-Times

Finding Iris Chang – Friendship, Ambition and the Loss of an Extraordinary Mind by Paula Kamen, Da Capo Press, distributed by Palgrave Macmillan

The Woman Who Could Not Forget: Iris Chang Before and Beyond the Rape of Nanking – A Memoir by Ying-Ying Chang, Pegasus Books, published May, 2011