Make yourself clear

July, 2010, The Sydney Instiute Papers

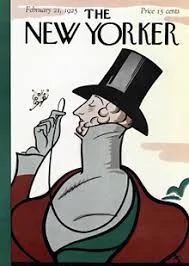

Harold Ross, the Colorado high-school drop-out who founded The New Yorker magazine in 1925,was to the pursuit of clarity what a bloodhound is to detective work.

He once looked over a short memoir by Vladimir Nabokov which was to be published in the magazine in the early Fifties. It was called “Lantern Slides” and was about Nabokov’s idyllic childhood in pre-revolutionary St Petersburg.

The piece is rich with emotive moments: thirty human hearts beating; the local concord of summer birds; the hullabaloo of bathing young villagers … There were “voices speaking all together, a walnut cracked, the click of the nut-cracker carelessly passed …”

Ross read the passage carefully. The “the” with “nutcracker” bothered him. He wrote on the galleys: “Were the Nabokovs a one-nutcracker family?”

Ross – whose magazine became one of the most respected of the 20thcentury - mostly stood for all that was good in writing and clear communication. He was addicted to Fowler and adored its four-page discussion on the uses of “that” and “which”. He wanted his new magazine to be “a reflection in word and picture of metropolitan life… It will assume a reasonable degree of enlightenment on the part of its readers. It will hate bunk.”

And yet, the in-house editing style at The New Yorker became so refined it could be as confining as bonsai. Nothing was to be left unexplained or up-in-the-air; no reader should ever have to fret their brow and wonder … Ross’s editors, following the leader, were as busy as anteaters as they foraged through copy for missing details.

(The habit caught on in America. I once worked with an editor from Time Inc who, in a tantrum, threw out a colour piece about a Wild West actor because no-one could tell him the name of the man’s horse.)

Clarity tackles Everest

I came across the nutcracker story in a history of The New Yorker written by American journalist Ben Yagoda, About Town (Scribner, 2000). I read it with delight. If Ross’s “fanatacism about language, his drive for correctness and transparency in writing”, as another writer described it, could drive him to such an extreme, it was also clear that it was motivated by his concern for the reader.

In light of where we are now, Ross’s dedication seems admirable. Clarity is up against it these days.

Photograph by Markus Spiske, Unsplash

Universities have been mugged by post-modernism (although young academics, as rooted in po-mo as seedlings are in potting-mix, regularly claim they haven’t been). Under its influence, academic writing is too often an impenetrable thicket; armies could get lost in the paragraphs.

Meanwhile, commercial publishers no longer flush in shame if a finished book is littered with typos, malapropisms, unresolved plot-lines and tangled syntax. Just so long as the book is on budget and the marketing is in place.

In the media, the role of the line editor and sub-editor has been so downgraded it’s possible to read a news story and wonder blurrily if any human eyes – bar those of the original reporter – have seen it as it has progressed from computer to printing press to newsagent to your table.

With technology and the internet spurring things along, kids are encouraged to treat spelling and grammar as if they are optional. Already, teachers complain their pupils struggle to articulate their feelings and thoughts because they haven’t acquired the language skills to do so. A speech pathologist writes in The Sydney Morning Herald, “Talking seems to have gone out of fashion… Children aren’t describing any more how their school concert looked – instead they just email the photos.”

Equality isn’t always a good fit

At the same time, all voices – no matter how confused, uncivil or ignorant - are deemed equal. (And so, a guest on the ABC’s programme Q&A may be delivering an opinion, developed over years of research and experience, while anonymous tweets flit across the screen, sending up the speaker’s line of argument. The ABC says it wants tweets that “inform and entertain” - my italics - “our broader audience”.)

Against that, reading Yagoda’s tales of writers and editors musing over what the reader will and won’t understand is like escaping the toddlers’ playground.

Or better, arriving in the study of one of The New Yorker’s most loved writers, E.B. White.

White wrote for the magazine for most of his life, from 1926 until his death in 1985. He too could be dismayed by the anteaters.

He complained to Ross after an editor changed the word “hen” in his copy to “her”. White’s piece was about pigeons and squabs; a hen, it might be thought, was a reasonable inclusion. But no. In despair, he noted, “Ten years ago, I would have been reasonably sure it was a typo. Today, with pigeon-checking at the pitch it has reached, I can’t be sure … A writer loses confidence in himself. I am not as sure of myself as I used to be, and write rather timidly, staring at each word as it runs out, and wondering what is wrong with it …”

(To be fair, Ross worried about the anteating too. He fretted to H.L. Mencken in late 1948, “We have carried editing to a very high degree of fussiness here … I don’t know how to get it under control.”)

This is the E.B. White who wrote Stuart Little and Charlotte’s Web and whose unassuming, lucid, wry writing was instrumental in shaping the voice of The New Yorkerin the first place.

E.B. was also the White who later resurrected a primer written by one of his old English professors, William Strunk, turning it into The Elements of Style, that good-humoured guide to writing good prose that has now sold over ten million copies.

If anyone understood clarity, it was White.

“She found only two mistakes”

The carefully revised handbook with its numerous rules and asides has gone into four editions and multiple reprintings since its appeared in 1959. It has influenced generations of students, writers, teachers and readers, not just in the United States but around the world and here, in Australia. In fact, wherever people care about words.

Its status is now so cemented that over the years it has been turned into a ballet, a video, and an operatic song cycle - with percussion supplied by teacups, a typewriter and a duck call. An illustrated version of the fourth edition came out in 2005: a basset hound makes a point about commas; a portrait of a stern Simone de Beauvoir appears over the sentence, “She found only two mistakes”, an example of rule 20, keep related words together.

Last year, American writer Mark Garvey brought out a kind of biography of The Elements of Style. He called it Stylized and its frank subtitle is A Slightly Obsessive History of Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style (Touchstone, $39.99)

It turns out to be a white rabbit of a book. Read it, follow its leads, and it will take you down the rabbit-hole and into a world where people happily debate colons, commas and clarity.

In early June, I reviewed Garvey’s irresistible book for The Sydney Morning Herald, coupling it with Elmore Leonard’s Ten Rules of Writing (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, $22.99). I’ve since discovered an even bigger treat: a week spent reading nothing but Garvey, Leonard, Yagoda and The Elements of Style.

The books overlap like spreading branches of a family tree. E.B. White turns up in Garvey and Yagoda and, of course, in Elements of Style while Leonard is the natural star of his own guide, but gets a cameo appearance in Garvey. Meanwhile, Yagoda and Garvey both explore what it was that The New Yorker brought to thought and writing. Garvey insists, at one point that The New Yorker and Elements are genetically linked because of White.

All four books help explain why people write at all.

A procession of events

What Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usageis to the British, The Elements of Style is to Americans. As Garvey makes clear though, Elements is far more than a guide to grammar. Fundamentally, it is about sighting a line of order in the chaos. Its most famous rule is: omit needless words.

That rule is not White’s though. It belongs to William Strunk Jr who authored the original guide on which Elements was based.

In 1918, Strunk, an English professor at Cornell, one of the ivy-league universities on the east coast of the United States, self-published a 43 page quick reference guide to clear writing for his students. It was meant to make his life easier and marking papers simpler. The following year, White enrolled in his class and bought a copy.

Strunk and White remained in touch for the next several decades but White forgot about the “little book” as the students liked to call it until, well after Strunk’s death, a fellow Cornell graduate sent him a copy in 1957 as a memento.

Charmed all over again by the guide’s brisk rules and the memories it brought back of his “funny, audacious and self-confident” professor, White wrote an essay about the guide and its creator. An alert editor at Macmillan’s educational arm, Jack Case, spotted it. Case believed that if the guide was as good as White said it was, it would be worthwhile to republish it in an updated form and with White’s essay upfront.

The project took over White’s life. The first edition, published in April 1959, went into 25 printings and sold over two million copies. There was a second edition in 1972 and a third in 1979, which sold 300,000 copies in its first six months. (The fourth, in 1999, came out after White’s death.)

Students and teachers loved the little guide. While Strunk’s barks remained, White’s tone, and his experiences as a writer, added warmth and humour. He warned students to give up their reliance on adjectives and choose their nouns more carefully: “The adjective hasn’t been built that can pull a weak or inaccurate noun out of a tight place.” Avoid fancy words, he ordered. “Do not be tempted by a twenty-dollar word when there is a ten-center handy.”

The guide remained austere – although it gained 28 pages for its first edition – but the original four chapters covering form, structure, composition and the misuse of key words were revised for a Fifties audience and White added a fifth chapter, “An Approach to Style”.

A “pretty girl” causes trouble

Naturally enough, there were critics. The rules – do not break sentences in two; use the active voice – got up the noses of some. The post-moderns disliked its implicit acceptance that universal truths and rules existed. In the Seventies, feminists objected to the references to women with children, dishwashers and ironing boards. The phrase, “Chloe smells good, as a pretty girl should” caused special pique. (White hung on to her but after his death, in the last edition, Chloe became a more gender-neutral baby.)

Others criticized its WASP-y tone. One writer personified it as a bow-tied priss. Readers wrote triumphantly to point out contradictions and errors. “Do you think this dreadful little book will ever settle down and stay quiet?” White wrote plaintively to his publisher in 1960, a year after the first printing.

“No,” replied Case, “because English won’t.”

If Case had been a different kind of editor and man, The Elements of Style might have ended up very differently.

By the Fifties, English departments were already being taken over by what White called “the happiness boys”, academics who believed rules stopped creativity.

While White worked on the revisions, Macmillan consulted a few of them, taking soundings on the book’s eventual market. The teachers suggested that Strunk’s rules should be watered down; there should be more licence. When this was tentatively put to the normally mild White, he retorted, “This book is the work of a dead precisionist and a half-dead disciple of his, and it has got to stay that way… I cannot and will-shall not, attempt to adjust the unadjustable Mr Strunk to the modern liberal of the English department, the anything-goes fellow… I have seen the work of his disciples and I say the hell with him.”

“All right,” cheered Case, “let him take the offensive and whale hell out of ‘em.”

Why ground rules rule

Garvey believes that rules are in our DNA. From Moses’ Ten Commandments to Paul Simon’s Fifty Ways To Leave Your Lover, we humans seem to understand that we cannot “get on with the complexities of anything – writing, thinking, working, playing, for some of us even shampooing – without first coming to grips with a few ground rules.”

One professor from Indiana points out that Strunk didn’t invent the rules; he just identified them. “They’re built into the language. If you want to build a good chair, you’ve got to figure out how chairs work. In the same way, you’ve got to figure out how language works in order to use it.”

Mark Twain offered his own rules and there is plenty of overlap: “Use the right word, not its second cousin; avoid slovenliness of form”.

Elmore Leonard is just as gruff if more idiosyncratic: “Keep your exclamation marks under control.”

And back at The New Yorker, Ross was fierce about rules because he wanted his new magazine to cover any subject in the world. Therefore, he required order. The writers might eventually be delivering stories from Hoboken to Hiroshima to Harare but at least whatever was being written about would be grounded in a common set of rules, in a common usage guide, in a uniform sense of clarity.

What Ross knew, what Strunk and White knew, and what Garvey makes clear is that it’s only by sticking to the basic rules that writers gain their freedom. Just as birds co-exist with gravity, friction and wind-forces, writers are kept aloft because the rules let them do so.

There is still the plight of The New Yorker writers to be considered, as they worked through the penciled queries on their ms. Indeed, it’s the lot of any writer with editors trained that way.

The invention of saddle-bagging

I once worked with a bunch of terrific, hard-nosed American journalists from the American magazine, People. Time Inc, the parent company, was then rolling in money. It had decided to start a local version here – Who Weekly – and it had sent the writers and editors over to live the life of Riley, on the harbour, on expenses, while they coaxed house-style into the new magazine and its Australian hires.

They introduced me to the practice of saddle-bagging. That is, when layers of editors justify their pay by demanding details. A sentence might start out as: “Joe Blow went to the store to buy some eggs” but it would end up as, “Joe Blow, who was 180cms tall with brown eyes and buck teeth, once went down to the shops, which were a kilometre away, on a cold 14C day, to buy six eggs so his mother, who was a widow, could scramble them.”

The sentences sagged like old Mexican mules. Worse, the writers had learned to head off the editors by censoring themselves. Maybe they knew that such and such an actor had once learned to ride an elephant. Would they mention that? Not unless they also knew who the elephant’s mother was and what size shoe she took.

The search for clarity in extraneous detail is as counter-pr oductive as muddiness or ignoring grammar. They are produced by a similar mind-set: one that doesn’t quite get what communication is, and where it leads.

Absolute clarity is a myth

Yagoda writes at one stage: “If they understand anything, writers know that the world is not characterized by absolute clarity.”

In fact, writers atThe New Yorker, did stand up to the streams of queries. Ross – whose regular interjection on a manuscript was “Who he?” - once questioned short story writer Sally Benson about a character who lived in a mountainside cabin. He asked, relates Yagoda: “How he come to be living on mountainside?” Benson snapped back, “I don’t know how he came to be living on a mountainside. This is just a story I made up, and I didn’t make up that part.”

How much should we expect readers to just get? Certainly, there were many New Yorker writers who were annoyed that apparently the “reader must never have to pause to think for a single second, but be informed and re-informed comfortingly all the time…”

The practice is far worse today as newspaper and magazine bosses watch their journals compete with YouTube, DVDs, twitter and SMS. Once it was accepted that readers had large vocabularies, owned dictionaries and didn’t mind thinking. No such luck now when readers are treated like infants who might squawl their heads off if they find a chunk in their pureed vanilla custard. Worse, worry the bosses, they might refuse more custard.

Give ‘em pix. Big ones. Keep it simple.

But is this kind of simplicity about clarity? Or is it dumbing down to the point where sentences have to be as obvious as blunderbusses?

A diet of only ten-cent words can make the brain feel short-changed.

How to think more clearly

Intriguingly, there does seem to be a neurological connection between writing clearly and thinking clearly. One professor, Isabel Hull in Cornell’s History department assigns Elements to her students because of its pithiness. She tells Garvey, “I receive comments from past students, all of whom without exception praise the improvement in their writing, and consequently in their thinking, from following these principles in my classes.”

All writers know that writing is rewriting. Not just because of the polishing but because the very act of writing seems to unleash thoughts you didn’t know you had.

Not everyone wants clarity of course. Don Watson has pointed out in his best sellers, Death Sentence and Watson’s Dictionary of Weasel Words that we live in a world of jargon where official statements and company mantras are designed to disguise and bamboozle

We’ve become inured to seeing the porkies told in public by corporations, politicians and bureaucrats explained away as “spin”. Oh, that’s okay then. Clarity may be the very thing that is now disliked on a board, in a wannabe politician, in an office or in a new staff member.

E.B. White once replied to a reader: “There are very few thoughts or concepts that can’t be put into plain English, provided anyone truly wants to do it. But for everyone who strives for clarity and simplicity, there are three who for one reason or another prefer to draw the clouds across the sky.”

Who wouldn’t want truth? (Lots of people)

The disconcerting thing about clarity is that it tends to lead to truth.

So if post-modernism insists there is no such thing as truth and modern managers run away from the truth, who needs clarity?

There’s another way to put that: if clarity helps us get to the truth, what is the point of muddy post-modernism and muddier modern management?

Clarity is a tough taskmaster. You either know what you’re trying to say, or you don’t. You’re either telling the truth, or trying to fudge. A commitment to clarity doesn’t permit the let-out clauses and escape routes that po-mo, spin, hype and moral relativism offer. No wonder the latter are more fashionable than the former.

In his biography of George Orwell, Bernard Crick describes the author, in 1937, watching the approaching war and the surrounding faff: “[Orwell] was beginning to see the connection between clarity of language and truth…”

Strunk and White never saw their rules as bossy; they wanted to help writers find their voice. And to find something else too, and that turns out to be the theme of Garvey’s book. He develops it subtly but tenaciously through his 209 page history.

“The moral thread running through The Elements of Style is undeniable.”

He writes, halfway-through, “Thrumming away inside this book about style is a most unstylish idea, but an idea that is also one of the most durable, encouraging and commonsensical notions ever to inspire a student or fire the mind of a writer: the belief that careful, clear thinking and writing can uncover truth.

“To believe in Strunk and White is to believe that truth exists, and that commitment to clarity is the path to it.”

White, not surprisingly, puts it even more simply: “If one is to write one must believe - in the truth and worth of the scrawl.”

This article was first published in The Sydney Institute Quarterly, Issue 37, July 2010