Seeing red

May, 2010, Good Weekend

In 1975, Truman Capote’s story-telling took him into dangerous territory.

A notorious gossip who loved the socialite life, Capote had decided to share with his readers a number of confidences that his gal pals, the privileged matrons of New York’s upper crust, had passed to him as he nestled with them on the plump banquettes of La Côte Basque, then on East 55th Street.

These women were social legends, daughters or wives of the rich and famous: fashion icon Slim Keith, Marella Agnelli, Carol Matthau, Gloria Vanderbilt. Capote with his sly tongue and early fame amused and flattered them. They responded with invitations, and secrets abut their set which Capote was now about to relay to his readers.

Capote was hungry for material. For years, the author of Breakfast at Tiffany’s and In Cold Bloodhad been promising his readers and friends he was writing a novel. That late New York autumn of the mid-Seventies, Esquire magazine published a tantalising excerpt from this supposed work in progress, Answered Prayers. Capote called it La Côte Basque 1965, and it featured, among other notorious incidents, a wealthy Jewish businessman made foolish by infidelity.

A powerful husband’s unfortunate escapade

A colossus of the newly dynamic corporate world, the businessman had invited a woman to his suite at The Pierre hotel for a nightcap of rumpy-pumpy while his wife was out of town. The woman, an East Coast Brahmin socialite, had bled all over his sheets. It turned out she had her period. Capote makes it clear in his story that her indiscretion had been a calculated gesture of casual contempt.

In November 1975, Esquire dropped a bombshell on New York society.

No-one has ever known, for sure, the real identity of the woman. The man, however, was William S. Paley, founder of television and radio network CBS, employer of newsman Edward Murrow. In haste and horror, Paley the mogul spent the rest of the night, once his visitor had left, trying to wash and dry the sheets before his wife came home the next morning. Sluicing them in the bathtub using a tiny cake of flowery Guerlain soap, shoving them in the oven to dry…

The wife was Babe Paley, one of the most elegant women of her day and a close chum of Capote.

Once the story was published in Esquire, and people had worked out who was really who, Capote’s goose was cooked. Paley and her friends, stung by his betrayal, shamed by the revelations, excommunicated the writer from New York society. He was never allowed back in.

It was little wonder the immaculate Babe was so mortified. Her husband's adultery was one thing: his lover's female functions spread out over her bed’s linen sheets - and the pages of a popular newsstand magazine - were another.

I can still remember that issue of Esquire. I was a very young newly-wed in Perth, buying smart American magazines and dreaming of sophistication. What floored me about Capote's story was the plot’s pivot – menstruation - and that such an anecdote was appearing in a magazine usually devoted to men, power, black tie and martinis.

Esquire was aimed at a certain kind of man - and suddenly it was running a story on menstruation?

After all this time, I can think of only two other occasions when menstruation has made it into pages that have become as widely read. Anne Frank, on the verge of puberty, wrote wistfully about periods in the diary she kept while hiding from the Nazis in Amsterdam. “Oh, I am so longing to have it too; it seems so important,” the doomed teenager wrote on October 29, 1942.

“He’s a three-pad man…”

In 1978, American feminist Gloria Steinem wrote her astoundingly funny send-up essay, “If Men Could Menstruate”, first published in Ms magazine and republished countless times since. She argues that if men had periods, they would see bleeding as a sign of power; they would set up national research institutes into monthly cramps; maxi-pads would be named after swaggering cinema heroes. Sample: “Menstruation would become an enviable, boast-worthy, masculine event. Men would brag about how long and how much ... Street guys would invent slang ('He's a three-pad man') ... "

But men don’t menstruate and proscriptions against menstruating women – what they are permitted to do and not do – can be found in most religions and cultures. The warnings go back to Pliny the Elder in Ancient Rome who claimed with a straight face that contact with menstrual blood turned new wine sour, led to barren crops, dulled ivory and even disgusted ants.

Something of that oppressive idea of contamination has lingered on forever.

Menstruation, a normal condition which affects half the world's population for around half their lives and which is a vital part of the process that allows human life to flourish naturally on earth, is mostly invisible in our literature, culture, art, politics, social life, interchanges, journalism ... In an age where nothing seems to be taboo, this is taboo in mainstream society: acknowledging that menstruation happens.

The world slides by that fact the way most of us gracefully ease past the giant displays of sanitary products in supermarkets. In 2007, a national survey conducted for Stayfree discovered that 92 percent of the women surveyed confessed they would rather talk about the intimacies of their sex-lives or child-birth than about periods. Thirty percent admitted to heaping groceries over their boxes of pads or tampons at the supermarket.

Sanitary product manufacturers recently came up with a bright new idea: noise-free tampons. That’s so that when a woman is using a public restroom and has to take a tampon out of its cellophane wrapper, no other woman in the next-door cubicles – that is, no other woman who has been menstruating since she was 12 or 13 and been using tampons forever – will hear the tell-tale crackle of the covering andknow that that woman has her period.

A Tampax website advises young girls, “practise with tampons at home. See how quiet you can be.”

Not a pad!

A couple of years ago, Melbourne writer Monica Dux, the 37-year-old co-author of The Great Feminist Denial, was at the Brisbane Writers’ Festival queuing for a coffee. Suddenly a woman slid up to her, tapped her shoulder and pointed surreptitiously at the floor. There lay a panty-pad which had fallen out of Dux’s wallet. “And it had been in my wallet forever,” says Dux, cheerfully forthright, “ so you know, it was a bit dusty and ink-stained …” What she remembers is the cloud of mortification that instantly settled not just over her but everyone around her. She says, her voice breaking with mirth, “It was as if half the café was going, ‘someone’s going to have to tell her!’”

In her book, Capitalizing on the Curseabout the massive products industry surrounding menstruation, American academic Elizabeth Kissling argues that how a society deals with menstruation can reveal a lot about how that society views women.

Oddly, there are signs that the embarrassment, far from receding in our emancipated times, is actually growing. Doctors report a recent, but growing, fad for something they call “super-hygiene” among their young female patients. It’s a fastidiousness about cleanliness, a kind of air-brushing of any bits of femaleness that might hint at the unpleasant realities of our biology.

Periods are seen as messy, shameful. One Melbourne gynaecologist tells Good Weekend of young female patients complaining bitterly even about their vaginal discharges although she tries to tell them they’re normal and are what keep the vagina healthy. “They just don’t want them; they think they’re disgusting,” she says. She is intrigued by the disjunct between the sexual sophistication of her young patients and their inhibitions and lack of knowledge about their bodies.

Are women menstruating too often?

Meanwhile, the menstrual cycle itself may virtually disappear in the light of new medical science. Researchers now claim that modern women who, unlike their ancestors, mostly have few or no children and spend little time breast-feeding, menstruate far too often for their own good.

Already, women, aided by the big pharmaceutical companies, can choose ways to have periods only four times a year, or even just once. Or not at all. Many medical experts argue this will save not just discomfort, but lives.

Last year, an unlikely book forced its way out of the close-meshed silence around women’s bodily functions and onto The New York Times’ bestseller list and Amazon’s top 25 in its first month. It’s called My Little Red Bookand it’s an anthology of first person pieces: women writing about their first period.

It sounds like a conversation stopper but the anthology’s young editor Rachel Kauder Nalebuff, and her publisher, Jonathan Karp, the wunderkind creator of the exclusive imprint, Twelve, part of the extensive Hachette publishing group, knew what they were doing.

Nalebuff, now 19 and at college, with a new edition just out, has been collecting the stories since she was 12. On the phone from San Francisco, she was tart. “Periods themselves don’t really interest me … It’s what they signify to different women. That’s where I think there’s power.”

Nalebuff had been stunned when, after she’d had her own first period in excruciatingly embarrassing circumstances that turned – more excruciatingly - into family dinner-table anecdote, her great aunt Nina confided her own story. She had got her first period in 1942 as she and her family were fleeing Poland, and the Jewish deportations under the Nazis, by train. At the border crossing with Germany, the train was halted and the family ordered to strip for a search. Thirteen-year-old old Nina had her yellow star of David secreted in her shoe. In terror, she peed herself and then discovered – more fear, more panic – that her pee was blood-stained. Heedless of the guns and uniforms, she raced for the privacy of the train, her mother behind her. The disgusted guards retreated. The family got to Belgium.

Anne Frank wrote wistfully of wanting her periods to start in a diary she kept as she and her family hid from the Nazis. The diary has sold millions of copies since her father had it published in 1947. Anne Frank died in Bergen-Belsen just months before the camp’s liberation.

Nalebuff couldn’t believe her relative had never related this riveting story to anyone before. Sensing hidden treasure in such untold tales, Nalebuff approached first, her friends and other relatives for their experiences; then later, strangers, writers, including Steinem who, eventually, gave her an updated version of her classic essay.

Hard not to laugh

In several of the 92 pieces, the writers confess they were convinced they were dying when their period arrived. Amy Lee, now a social justice educator, was panicked when she saw the small stain on her cartoon-printed underwear. She had no idea what a period was: her Korean parents had never let her go to sex education classes. “My parents spoke limited English and they only needed to understand one word: sex. So while the girls learned about periods, pads and puberty, I sat with the boys and watched Big Ben, a movie about a brown bear.”

Another contributor, Ellen Devine, now an English teacher in Connecticut, discovered tampons when she was only four, snuggled on the floor of the upstairs hallway, secretly watching her mother in the bathroom. She loved the daily ritual until the day her mother did something astonishing: to her incredulity, her mother apparently removed a hot-dog from between her legs. “It opened up a world of questions,” Devine writes. “Why did my mother store hot dogs in her vagina? Did she always store one in there? Was she able to store more than one? … Did other women keep hot dogs in their vaginas?”

Nalebuff’s anthology includes stories from around the world which allows it to go beyond the light-hearted and touching to explore the ramifications of menstruation in continents where women can't afford or obtain sanitary products. Young girls duck several days of school every month as a result. Often, they just pull out altogether. In Asia and Africa, women use rags but then - because of stigma and often poor access to clean water - cannot wash, dry and store the rags hygienically. Infections are rampant.

Who would ever have thought any of this was happening? Certainly not western men. Not even western women.

Enter Mr Karp

At her tone-y private school, Choate Rosemary Hall in Connecticut, Nalebuff became known as “Period Girl”. Undeterred, and unfazed by early knockbacks from various publishers, the unstoppable Nalebuff got herself an agent. Within a week, she had her publisher, young Mr Karp whose imprint chooses to publish and promote just 12 books a year.

She says astutely of her triumph that, “It says something really important about how our media works and the way women’s roles end up playing out in large companies. All the women [publishers] I pitched it to, they think, my male boss isn’t going to like this or my male readers are going to be grossed out by this. But the male bosses, if they feel fine about it, they’re going to go for it.

“[Men] are not going to be worrying about what the other half is going to think … and honestly, that’s why women don’t talk about their periods in the first place … Once you have a guy in the room, you know, mum’s the word.”

Years of feminism and the new in-your-face go-grrrrl raunch don’t seem to have been able to change attitudes one jot. The videos on the book’s website, www.mylittleredbook.netwhere young girls talk about their recent first period, are an eye-opener. For all the in-your-face blogs like Pussy Pirates, which are read by just a few, and author Charlotte Roche’s explosive literary best-seller Wetlands, which leaves no female orifice unexplored, tested and tasted, these teenagers of the coolly knowing iPhone, Facebook era, still seem to be as awkward and sweetly abashed and shamed as girls 50 years ago, 100 years ago, 1000 years ago ...

Meanwhile, when I first pitched Nalebuff’s book to staff at a local young women’s magazine as a possible subject – it was published here mid-2009 - they are genteelly appalled. Why would anyone want to read about, they ask.

Get over it, world

Nalebuff tells me exasperatedly, “The stories [in My Little Red Book] let women relate a moment they haven’t been allowed to talk about. Menstruation should be viewed like blowing your nose or child-birth, as a fact of life, something that happens and that may be physically unappealing but which has a deeper meaning and it’s something important that unites all women.”

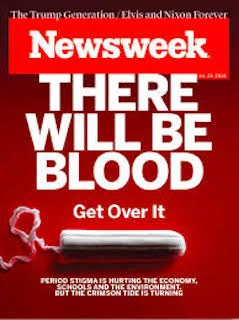

In 2016, news magazine Newsweek took on the issue.

But maybe women don’t have to menstruate after all.

In 1999, Brazilian endocrinologist Elsimar Coutinho co-authored the book Is Menstruation Obsolete? He argued that, in history, women menstruated far less because of later onset of puberty, many more pregnancies and longer periods of breast-feeding. Those women might have menstruated around 100 times in a lifetime; the modern woman has her period 400 to 450 times. Coutinho believes, as do many others, that that constant cycle means women are vulnerable to a range of physical disorders from anaemia to arthritis and uterine and ovarian cancer.

Coutinho’s point was taken up by author Malcolm Gladwell in a March, 2000 piece for The New Yorker. Gladwell also found a medical statistician and cancer researcher, Malcolm Pike, who connected constant monthly ovulation – and the consequent cell division caused by the hormonal surges - with a higher risk of breast cancer. The professor exclaimed, wrote Gladwell, “… the modern way of living represents an extraordinary change in female biology. Women are going out and becoming lawyers, doctors, presidents of countries ...They ovulate from 12 or 13 until their early thirties. Twenty years of uninterrupted ovulationbefore their first child! That's a brand-new phenomenon!”

Stop menstruating now

For the past several years, the billion dollar pharmaceutical industry has been working on ways to turn menstruation into an anachronism, encouraging women in the United States with marketing and re-packaging to adopt the contraceptive pill to stop “periods” for ever-longer lengths of time. (The pill actually stops ovulation so the fourth week of bleeding in the cycle is not a real period; it occurs because of withdrawal from the hormones. The withdrawal week was only included in the pill cycle by the creators so the process would appear “normal”, and reassure both women and the Catholic church. The later remains unappeased.)

Women have often manipulated pill packets, running them on, to avoid having a period at key times or to treat severe menstrual pain, endometriosis or migraines. Now some women just want control over their wayward, messy, unpredictable bodies, and medical science is giving them an out.

In 2003, in the US, one company Barr Laboratories took the low-dose oestrogen and progestin contraceptive pill and repackaged and remarketed it as Seasonale, a pill to be taken continuously for three months at a time by any woman who wanted less frequent periods. “Fewer periods, more possibilities,” was the marketing line. Three years ago, in 2007, Wyeth introduced another “new” pill to the US, Lybrel, which can be taken for 365 days of the year, eliminating periods altogether.

In more pragmatic, down-to-earth Australia – where the pill is the most popular choice for women using contraception – medical advice for years has been to simply take the existing low-dose pills for three cycles without stopping. Family Planning Australia has been teaching women the practice since the Eighties. Many women don’t even bother to ask a doctor; they work it out for themselves.

It has been a quiet revolution. To many of us, it sounds radical. To plenty of others, those in the know and who aren’t trying to get pregnant, it’s old hat. “Is menstruation obsolete?” asks FPA’s Dr Christine Read rhetorically. “It can be. You don’t have to have it.”

Sexual health physician, Dr Terri Foran who lectures at the School of Women’s and Children’s Health at the University of New South Wales, and is a former medical director of Family Planning, NSW, is matter of fact: “The only reason for menstruation is to set up the uterine lining for the next possible pregnancy so if we’re only having one or two babies in our lives, there’s no need for that to be happening constantly.

“When I say to patients that it’s not biologically necessary, you can see the lights go on. Managing menstruation is a drag. Many feel: why bother having periods at all? Young women are more active; they want control of their bodies.”

What young women are doing

Will the choice not to menstruate become as accepted as say, women deciding to shave their legs and armpits? Perhaps it will soon be considered “gross” to be the kind of woman who chooses to still have a period 13 times a year.

Foran says around a quarter of the young women on the pill she sees at her inner-city Sydney clinic are using it to suppress menstruation. Dr Elizabeth Farrell, of Melbourne’s Jean Hailes Foundation for Women’s Health, says she has noticed increased interest in the last ten years in the practice and while she might have to tell older women about it, as a treatment for medical problems, it’s the younger women and teenagers who come to her independently, asking about it. Read says approximately ten to 20 percent of FPA patients on the pill, of all ages, extend their cycles.

But, surprisingly, there are no official statistics and nor have any long-term studies of continuous pill use been done anywhere. Seasonale and Lybrel only conducted year-long studies because they were using an already-approved drug.

For that reason, there is now intense, sometimes vehement, debate about the effect of extended contraceptive pill use on a woman’s health. The arguments from each side are persuasive and often directly contradictory.

“Largest uncontrolled experiment in the history of medical science”

Foran, like others, argues the pill has been used safely for 40 to 50 years and that, in effect, is a long-term study. But there is a much cited quote from staunch critic, American psychiatrist and author Susan Rako, founder of the activist group Women’s Health On Alert, who says, “Manipulating women’s hormonal chemistry for the purpose of menstrual suppression threatens to be the largest uncontrolled experiment in the history of medical science”. She lists possible risks running from heart disease, stroke, osteoporosis and cancer to lower libido due to lower levels of active testosterone.

Canadian endocrinologist Dr Jerilynn Prior of the University of British Columbia tells Good Weekend she believes her research and data show a link between non-ovulation - occurring either naturally or through use of the pill - and lower bone mineral density. Controversially, she pins it down to lower levels of progesterone, and is especially concerned about the effects of the pill in young women who would normally still be laying down bone tissue. She also worries about what effect the pill’s hormones could have on developing breast tissue in young women, and also on the ovulation cycle when it hasn’t had time to become established.

A medical reporter hazards there could be “hormonal surprises in the wings” if menstruation, and all that goes with it, is suppressed long-term, and a colleague of Prior talks of the “hubris” of tampering with the endocrine system. “In complex systems, it is very hard to do just one thing,” researcher Christine Hitchcock explains.

But, argues one of Australia’s foremost experts in the area of menstrual suppression, Professor Ian Fraser, professor in reproductive medicine at the University of Sydney, our society has been unknowingly tampering with the reproductive system for the last 100 years, in the way women have their babies much later and do little breast-feeding.

“Women now have many more periods than previously, and that means big swings in hormones which occur repeatedly every month.”

The cancer risk of constant ovulation

That, he says, dramatically increases the risk of breast, ovarian and endometrial cancers and other reproductive diseases in women who are susceptible genetically. “These hormonal swings lead to frequently repeated cycles of cell growth and regression, which can eventually lead to uncontrolled changes in cell growth and function - and therefore, sometimes to cancer.

“Women aren’t really designed to have these swings 450 times in a lifetime,” he points out. “The idea that regular menstruation is a good healthy clean-out is a myth. So then you’ve got to say: are there any adverse consequences of that ‘tampering’ by society in the way in which reproductive experiences have changed, and should we do something to reverse those consequences or ameliorate them without doing harm?

“A lot of women would be better off having fewer periods.”

An impressive list of benefits is also claimed for the pill as a result of recent studies: dramatic reductions in lifetime risk of ovarian and endometrial cancer; reductions in colorectal cancer; lower incidences of benign breast disease, fibroids and endometriosis; while conditions like acne, period pain and pre-menstrual syndrome can be helped substantially. Fraser does not believe there is evidence the pill affects bone-density one way or the other.

Major, long-term studies that examine effects around the body would help clear the conflicting claims between the two camps, but big funding would be needed and resources are always limited. It’s also very difficult to get women to stay on studies that might last 30 years, says Fraser.

Women’s business doesn’t attract business

Kaisu Vartto, CEO of Sexual Health, Information Networking Education, South Australia, or SHine SA, confided frankly, “Nobody thinks it’s sexy enough to do research on it. It’s women’s business.”

Meanwhile, the idea of suppression still plays uncomfortably close to the notion that a woman is trying to rid herself of something she feels – or has been made to feel - is vaguely disgusting, burdensome or unclean.

American health groups were worried, when Seasonale launched, about the effect on impressionable teenagers and young women. A study conducted four years after the product’s launch in the States found that the most common reason American physicians prescribed extended pill use to women aged 15 to 24 was not for medical treatment but the patient’s personal preference.

While many doctors believe tri-cycling is safe – “fantastic” as Farrell puts it for treating her patients with severe menstrual disorders – the trend towards super-cleanliness amongst young women may be acting like an intersecting riptide.

Doctors and specialists describe young women patients practising a kind of sanitisation process on themselves. Many young women now don’t just shave their underarms and wax their legs and their bikini-line; they wax their forearms as well and any other bit that looks hairy. Foran says of her patients, that she hasn’t seen anyone under 30 with pubic hair in a long time. “Most of my younger patients wax, either completely or maybe just leaving a tiny strip.”

If Foran hands them a pad after a procedure, they’ll look at it in wonder. What’s this? They’ve been using tampons forever.

Dry as a chip

Like Farrell, she is bemused by the way her young patients, squeakily clean, are horrified by their discharges. Many insist on routinely wearing a panty-liner each day. “It’s not a healthy thing to do,” she says. “The vagina can’t breathe, they can get dermatitis. But when I say that, these young women will ask ‘but how do I stay clean and dry?’ I have to explain that a discharge is how the vagina cleans itself; it’s what allows you to have sex.

“But,” she adds memorably, “they want to be as dry as a chip down there.”

“Women are fairly sensitive,” she adds. “A lot of this careful cleanliness is actually driven by women themselves, like the craze for high-heels. We’re socialized from a very early age that our worth is to do with how other people think of us.”

In fact, many women manage their period easily, can feel energized by it and see it as a reliable monthly indicator of their general health. The irrepressible Nalebuff provides her own view at the end of our interview, chirping in her sing-song American accent, “It’s hard to say this scientifically … but having a period every month and knowing that your body is healthy and in tune, and that you’re not pregnant? That’s priceless.”

She has included her younger sister Zoe’s first period story, from 2005, in her anthology, and it snappily demonstrates how things change – but don’t:

“Glittergrrrl007: OMG did u get ure period????

“BananabOat: Yea, I’m pissed.

“Glittergrrrl007: LOL

“BananabOat: Well only 40 more years 2 go!!”

Or not.

This is a longer version of a story that was published in Good Weekend on May 1, 2010. Intriguingly, I had the same experience as Nalebuff in trying to pitch this article to various female editors and staff, including some working on a women’s magazine which claimed to empower its readers. The first editor to say yes was a man, Roy Eccleston of the Adelaide Advertiser (for a shorter piece), and then Judith Whelan on Good Weekend also said yes. The article was reproduced later – at this length – in Best Australian Essays 2010. Again, edited by a man, novelist Robert Drewe.

My Little Red Book, edited by Rachel Kauder Nalebuff, published by Twelve, Hachette, rrp, $19.99

The Centre for Menstrual Cycle and Ovulation Research – www.cemcor.ubc.ca